FOR INVESTORS

Governance and Voting Solutions for Smarter Decisions and Seamless Workflows.

FOR COMPANIES

Corporate Governance Solutions to Advance Governance-Related Strategies.

United States and Canada 2026 Benchmark Policy Guidelines Webinar

Watch members of our governance, ESG, and remuneration experts provided an overview of the key updates to our 2026 Benchmark Proxy Voting Policy Guidelines for Continental Europe and the UK.

United States and Canada 2026 Benchmark Policy Guidelines Webinar

Watch members of our governance, ESG, and remuneration experts provided an overview of the key updates to our 2026 Benchmark Proxy Voting Policy Guidelines for Continental Europe and the UK.

Continental Europe and United Kingdom 2026 Benchmark Policy Guidelines Webinar

Watch members of our governance, ESG, and remuneration experts provided an overview of the key updates to our 2026 Benchmark Proxy Voting Policy Guidelines for Continental Europe and the UK.

Continental Europe and United Kingdom 2026 Benchmark Policy Guidelines Webinar

Watch members of our governance, ESG, and remuneration experts provided an overview of the key updates to our 2026 Benchmark Proxy Voting Policy Guidelines for Continental Europe and the UK.

The Climate Intelligence Landscape: Current Limitations and the Road to Improved Financial Signals

This article explores the type of signals investors seek when it comes to climate intelligence research for their portfolios and the status and limitations of the current data landscape.

The Climate Intelligence Landscape: Current Limitations and the Road to Improved Financial Signals

This article explores the type of signals investors seek when it comes to climate intelligence research for their portfolios and the status and limitations of the current data landscape.

The Evolving Investor Approach to Climate: Examining Shareholder Proposals as a Forum on Climate Change, Reporting and Emissions

Investors’ consideration of climate and other environmental, social and governance (ESG) matters has evolved significantly in recent years.

The Evolving Investor Approach to Climate: Examining Shareholder Proposals as a Forum on Climate Change, Reporting and Emissions

Investors’ consideration of climate and other environmental, social and governance (ESG) matters has evolved significantly in recent years.

ABOUT US

Why Choose Glass Lewis?

Founded in 2003, Glass Lewis operates globally with offices in North America, Europe, and Asia Pacific, including locations in San Francisco, Toronto, London, Limerick, Karlsruhe, Paris, Sydney and Tokyo. Our innovative solutions support governance and stewardship efforts worldwide.

1300+

Investors Globally: Leveraging Proxy Paper research and custom policy recommendations.

2300+

Corporate Issuer Clients: Engaging on material governance and disclosure practices.

$40 T

In Assets: Managed by our clients across 100 global markets.

30000+

Meetings Annually: Covered with rigorous research and recommendations.

~3 Weeks

Corporate governance research reports delivered ~3 weeks in advance of AGMs, in most markets.

1400+

Research Team Engagement Meetings Held with Corporate Issuers. (2024)

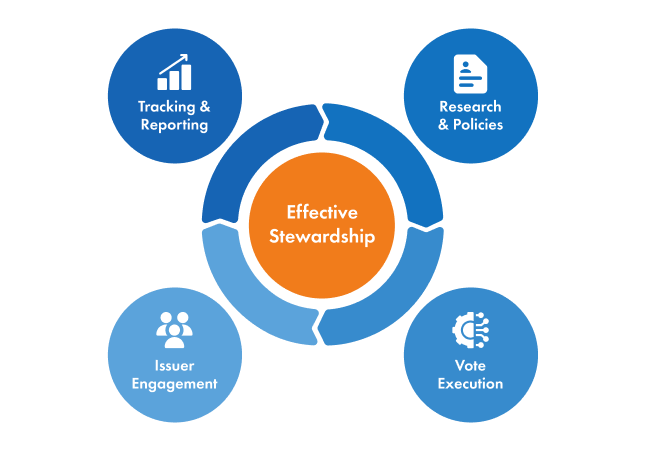

Learn how Glass Lewis supports corporate governance and stewardship best practices.

Book an initial conversation.